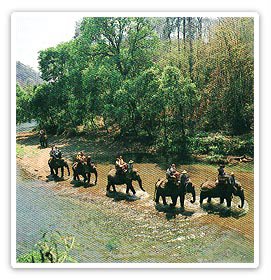

Elephant Riding in Thailand

Hand-feeding a hungry elephant is an unnerving experience. At the first whiff of a banana, its leathery gray trunk snakes out, probes the air and sucks it from your hand with a squelch. It is like shoving fruit into a wet vacuum cleaner nozzle.

Hand-feeding a hungry elephant is an unnerving experience. At the first whiff of a banana, its leathery gray trunk snakes out, probes the air and sucks it from your hand with a squelch. It is like shoving fruit into a wet vacuum cleaner nozzle.It may be unpleasant, but if you're about to plunge into the jungles of northern

Just half a day's jeep ride from the city of

"Hold onto its forehead and dig your heels into the side of its neck," said Chan, my enthusiastic guide. "Kick left to go left and right to go right. And if he stops to eat bamboo, just give him a good slap."

Steering an elephant sounded easy enough. But 10 minutes into the trek, my thighs were chafing on Dumbo's course hide. And despite his frequent snack stops, I was wary of slapping a beast strong enough to knock over a tree. It wasn't luxury travel, but as we searched in the tropical heat for a Lahu village — one of the largest hill tribes in

It is estimated that some 550,000 hill tribe people live in the mountainous regions of

Most of these chao khao (mountain people) have no nationality, and instead live according to tribal law in their jungle clearings, with their own language, dress, customs and religious beliefs. Most have no electricity, running water or sanitation, and resist assimilation into mainstream Thai society and the practices of the 21st century.

Although you can strike out alone in search of the hill tribes, armed with a map and a phrase book, it is inadvisable. Clashes between the Thai army and drug runners from

Just as I thought my thighs could take no more chafing, we broke through the lush forest into a jungle clearing containing around 20 bamboo huts, raised six feet off the dirt floor on poles. A dozen small children, dressed in the traditional black, blue and green homespun clothes of the Lahu people, raced toward our group of 12 sweaty and tired Westerners. As we dismounted, they gathered round, pulling the hairs on our arms and legs playfully, before growing shy and running away.

Beyond the huts, men and women toiled under the tropical sun, harvesting rice from tiny, tiered fields on the mountain slopes. Nearby, a man tilled the soil with an ox yoked to a wooden plow. These were the Lahu people, a 59,000-strong ethnic group originally from

Like the other main ethnic groups in northern Thailand — the Lisu, Mien, Hmong, Akha and Karen tribes — the Lahu primarily live off the land, eating a diet of rice, corn, chicken, pork, and whatever food can be found in the jungle. With no phones, computers, radios or televisions, their world is limited to the affairs of their village, population 150, and their neighbors in other jungle settlements.

After a simple but tasty meal of rice and vegetables, the village elders told us — through Chan, our interpreter — of the Lahu's tribal laws. With no regard for the regulations that govern mainstream Thai society, the Lahu marry and divorce with a minimum of fuss. A prospective groom merely pays his bride's family around $15 and throws a feast to formalize the marriage.

Unless he has a few hundred dollars saved up, which is unlikely in a subsistence economy, the husband must then live with and work for his new in-laws for a year, before he is free to set up home with his wife. And if he chooses to divorce, he merely seeks permission from the village chief and pays another $15 — half to the family and half to a village fund.

After a sleepless night on the hard floor of a bamboo hut, we left the Lahu people, and trekked on through the jungle, heading for other villages and tribes.

The paths that wind through the forest, past waterfalls, over streams and up the steep slopes of the mountains can be demanding. Would-be trekkers need to be reasonably fit, especially as you are expected to carry a backpack with enough clothes for three days.

But the pace is leisurely and there are frequent stops to bathe in rock pools, talk with people you encounter, and eat snacks of rice and noodles in villages en route.

A trek also offers a chance to walk through beautiful forests and jungle, with flora and fauna you would never see at home. It also gives you a window into an ancient way of life that still manages to flourish and retain its uniqueness in a modern world. On top of that, you learn how to steer an elephant, and you never know when that may come in useful.

source: USA Today

source: USA Today

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home